Lines in the Sand: Part 3

Changes to the UK’s political map and implications for the voice of communities.

26 April 2023

Swiss-based freelance journalist

Michael Woods

Photo: Nora Woods

The UK’s political map is under review. The next general election is less than two years away. When it takes place, parliamentary constituencies are likely going to change, some significantly. This is the case in my hometown of Southport, at least in my view. As I quickly discovered, in Southport and elsewhere, the news isn’t reaching everyone. Are communities being left out in shaping themselves and their future?

This three-part series is the story of my attempt to answer this question. In this final part, I look at local news decline, including what it means for democracy and community engagement in political boundary reviews.

I also explore what the future might hold.

Transparency note: This project uses generative AI. Click here to find out more.

News Deserts?

If the Boundary Commission for England’s suggested changes for Southport’s parliamentary constituency go through, my hometown’s parliamentary seat will soon grow.

I wanted to get a better idea of what this might mean for the places that will join the constituency. One such place is Banks, Lancashire. Jonathan and Janet live here. I managed to arrange a visit with them to hear what they thought of the changes.

Jonathan and Janet both grew up in the Midlands and moved to Southport in the mid-1980s. While the couple moved to Banks in the early 1990s, they feel strongly tied to Southport. “Our life has always been in Southport”, Jonathan told me, “everything we do is in Southport.”

Janet and Jonathan

Janet and Jonathan

Their home told this story too. On their walls, they had images of old Southport. They had a carving of the word Southport by their TV.

So what did the suggested changes mean for them? Jonathan said “we’d much rather be in the Southport constituency than in South Ribble, where we don’t feel any sort of allegiance really”.

However, when it came to the recommendation to move Ainsdale out of Southport, Jonathan had the same response as everyone else I talked to. “It doesn’t seem to make any sense to me, in that Ainsdale to me is very much an area of Southport.”

Jonathan also said something else that stuck in my mind. He mentioned the suggested move for Ainsdale wasn’t news to him. However, he thought it wasn’t an issue any more.

“My understanding was that they’d said no to it. It wasn’t going to happen. And then all of a sudden it seems to have resurrected again.”

This stood out too me as Jonathan is someone who’s interested in local government issues. He also worked for Lancashire County Council for six years.

I asked Jonathan where he gets local information.

“We used to get the Midweek Visitor”, said Jonathan. “And then we also got the Champion. The Champion was very useful.”

In part one, I mentioned that Dorothy from Ainsdale had learned about the changes in a local newspaper, which has since closed. This was also the Champion.

The last edition of the Champion was released last August. Soon after, the paper’s publisher went into liquidation. The Liverpool Echo reported trading conditions were to blame and that the company’s free local newspapers would no longer be delivered to around 165,000 homes.

The Champion’s former office in Southport

The Champion’s former office in Southport

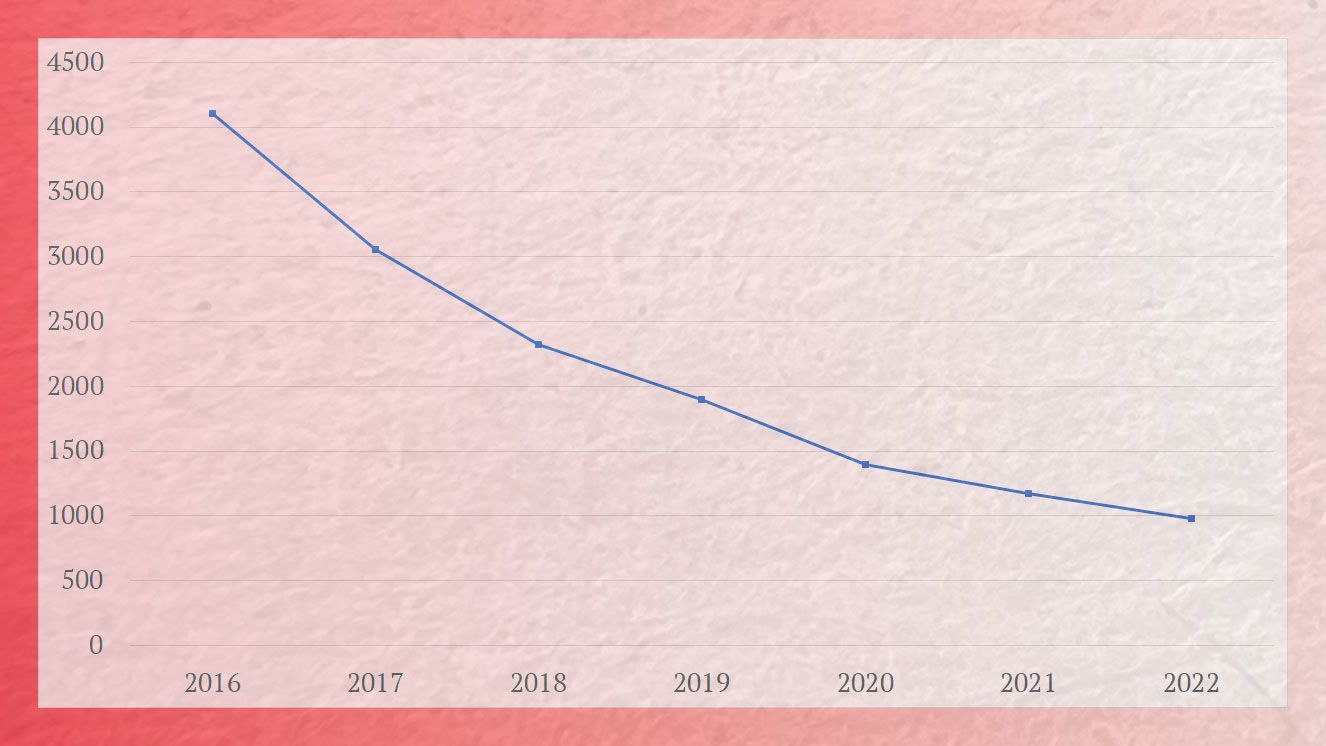

The Midweek Visiter, another free local paper for Southport, was shutdown by its publisher Reach in 2020. The town does still have one printed newspaper: the Southport Visiter. This is a paid-for title also published by Reach. But, according to media auditor ABC, the paper is down to a weekly circulation of 980 copies, including 13 subscribers.

To find out what had happened to Southport’s local newspapers, I talked to Andrew Brown. I managed to catch him on a busy day, when his phone was ringing non-stop. As well as holding other positions, he was the assistant editor for the Southport Visiter and Midweek Visiter in the 2000s.

Today, he runs a news platform that focuses on positive stories in the town. But he said he worked for the Southport Vister for a long time. When he started, the paper sold 20,000 copies a week, in a town of around 90,000.

“We’d get calls from newsagents to say that they’d sold out, so we’d have spare bundles of papers, and, you know, we always used to muck in. I used to chuck a couple of bundles in the car and go to Steve Baldwin’s newsagents on Eastbank Street. Here’s another couple of bundles, Steve. They were flying off the shelves.”

But things changed.

Southport Visiter Average Circulation Numbers

Source: ABC

Source: ABC

“The landscape is very different now from 20 years ago,” Andrew told me, “from even five years ago. I think the pandemic maybe accelerated things for the Champion. It certainly caused the Midweek Vister to close.” Andrew also wasn’t sure how long the Southport Vister will last, given its sales. “I do fear for towns,” he said, “but I think this is something happening across the country.”

According to news services covering the media industry, Andrew’s concerns are well-founded. HoldtheFrontPage reports last year didn’t just see the Champion shut down. While six local news outlets opened, over twenty closed. The PressGazette also reports that the BBC is planning local radio cuts, while Reach, which owns many local titles besides the Southport Visiter, may lay off hundreds of journalists.

These developments don’t follow a good period for local news either. The PressGazette says there’s “been a net loss of at least 271 print local newspaper titles” since 2005. Another article from the gazette explains local papers have had to consolidate to survive.

These trends are tied to the growth of social media and the internet, including their impact on newspaper sales and advertising income.

Image: AI generated by DALL·E

Image: AI generated by DALL·E

However, there may also be broader problems. Survey data from Oxford University’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism suggests there’s declining interest in news and trust in the media in the UK. It also indicates that news consumption has declined across the board, meaning social media isn’t filling the gap.

In response, the Charitable Journalism Project has produced a research report on whether “news deserts” are spreading across the country. This refers to areas where local news may have fallen away or even disappeared. The project found that social media is “now dominant in local news”, but it hasn’t replaced comprehensive coverage and has been linked with misinformation.

The communities the project talked to for its report also said local newspapers inadequately scrutinise local government, focus on clickbate and are overly negative.

The picture painted by the report is also bleak when it comes to people’s knowledge of local political and other current affairs. People sometimes appeared to be “unaware or confused about democratic developments”. One concerned local councillor in Barrow-in-Furness told the project that some locals only learned that their council was being abolished during canvasing for the new one.

“We are doing door knocking and we say ‘Will you vote for us for the new council?’, and they say ‘Well what is it?’ And we say ‘Well Barrow Council is being dissolved, Cumbria County Council is being dissolved and a new unitary body is being set up...’ And you can see them not grasping it”.

Those interviewed by the Charitable Journalism Project wanted local news for local people. This may conjure up images of the local shop in the League of Gentlemen, but perhaps that’s appropriate. Regardless, the project’s research suggests people want news which is locally produced, focused on local issues, trustworthy, professional and accessible.

Reading the report reminded me again of my conversation with Southport’s former MP John Pugh. “Southport’s had a little flurry of online news sites, but not one you’d call canonical that everybody goes to.”

He said you might learn about a car accident that’s happened down the road or see local news on Facebook if someone shares it. However, John suggested the existence of local newspapers often used to mean locals would hear about complaints about things like new cycle lanes. This was the case even if they weren’t interested in such goings on themselves. That’s not the case now. He said “people are just completely oblivious to things that may exercise and excite others.”

The Southport Visiter building. Closed in 2014, sold last December.

The Southport Visiter building. Closed in 2014, sold last December.

There’s also other concerns linked to newspaper decline and people getting more information online. For example, a recent Lloyds Bank’s study suggests 14 million people in the UK likely struggle with online services.

This is a real challenge as information is tied to democratic participation. In fact, the Charitable Journalism Project suggests the lack of coverage on local issues is leading to apathy and disinterest in local democracy.

Besides broader issues, these information scarcity problems could have an impact on political boundary change processes.

Research by the Electoral Commission has found that over 9 million people may be incorrectly registered to vote, or “not registered at all.” If a lack of coverage leads to apathy, people may be even less likely to register. This could then affect boundary changes. This is because it’s parliamentary voter registration numbers that the boundary commissions use to determine the size of constituencies.

Then there’s the simple point that if you don’t know about something, you can’t shout about it. You also can’t shout about something with any real impact if you don’t understand it. Given that the Boundary Commission for England uses feedback from the public in its decisions, a lack of knowledge may lead to communities being split.

People aren’t sure what the boundary changes mean. People also don’t feel heard when they give feedback. People also sometimes think their community’s concerns have been addressed when they haven’t. A lot of this is tied to a lack of information. This’ll probably lead to more confusion and frustration when new changes come through.

As John Pugh told me, “probably for the next twenty years, people will say, ‘well, you know, I live in Ainsdale, Southport,’ and then be surprised that they’re voting for the Sefton Central MP.”

Where Next?

On the day the public consultation for England’s parliamentary boundary review closed, the Labour Party released a report setting out proposed reforms for democracy and the economy in the UK.

With Labour still ahead in opinion polls, there’s a chance the party could form the next government.

In his speech for the report’s launch, Labour leader Keir Starmer talked about transferring power away from Westminster to give a greater voice to people closer to where they live.

He also spoke of a consultation about the proposals. However, in response to a question from the BBC’s Chris Mason about delivering the plans, Starmer said something that left me unsure what role local communities would play.

“So we’re not going to be consulting when we’re in power. We’re going to be delivering.”

Image of Keir Starmer: Courtesy Jeremy Corbyn/Flickr.

Image of Keir Starmer: Courtesy Jeremy Corbyn/Flickr.

Labour’s plan is to perform the consultation about the recommendations before they enter power. This made me think of the people I’d talked to in Southport about the boundary commission’s consultations. Apart from those in politics like John Pugh, hardly anyone had heard about them. Would people hear about Labour’s consultation?

Starmer also said he didn’t want to talk about boundaries. This came in reply to a question from the Yorkshire Post’s Mason Boycott-Owen. Starmer said “if we go down the rabbit warren of just talking about where the boundaries are, we’ll come out in five years time without actually having changed anything for people in the areas they live in”.

Image: mounsey/Pixabay.

Image: mounsey/Pixabay.

Given the problems facing local news, I was left with a concern that if Labour get in, a surge of new powers could be redistributed across the country without informed consultation with local people. This left me wondering if people at the local level, like Dorothy, would simply see possible reforms as just more change that’s implemented without the involvement of the communities it’s supposed to be for.

Reforms may come regardless. The Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee suggested late last year that there’s “overwhelming support” for governance reform in England.

However, the committee suggests there’s no consensus on what path to take. They also criticised the current government’s plans as insufficient and unlikely to be effective in tackling the existing governance system’s problems. Also, one of these problems is that “people in England increasingly feel that their voice is not being heard”.

So what’s on the cards for helping communities have a voice, or at least keeping them informed about coming boundary or other changes?

Recently, the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee released a report on local journalism’s sustainability.

Image: albersHeinemann/Pixabay

Image: albersHeinemann/Pixabay

Overall, the report suggests that existing forms of support are “not enough to stop the decline of local journalism.” The government has not yet responded to the report’s recommendations. However, the government may bring some relief if it passes a proposed law that seeks to address the dominance of technology companies like Google and Meta. This could help local and other news publishers to compete and survive online.

Still, it’s obviously difficult to say how much this will end up helping inform local communities.

Back in Southport, Andrew Brown is attempting to play his part in filling the news gap, even if this wasn’t his intention at first.

“I was made redundant from the Southport Visiter three years ago,” he told me. Andrew explained the Southport Visiter’s website had gone, being merged into the Liverpool Echo’s pages. There were still a few websites reporting on Southport, but Andrew felt that coverage was generally negative or about crime. “So, I started Stand Up For Southport as a website that would cover the positive side of the town.”

This was just a hobby for Andrew at first. “I was absolutely looking for different jobs”, he told me. However, things changed. “It’s really taken off,” Andrew said, “and I’m really pleasantly surprised how much it’s taken off.” Andrew’s website is even starting to make an income for him.

Nic Newman from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism suggests a positive story approach like Andrew’s is increasingly being taken up by publishers, including as a way to deal with news avoidance.

Me reading the Southport Visiter. Photo: Ray Woods

Me reading the Southport Visiter. Photo: Ray Woods

I also found some positive stories refreshing for myself, particularly when it came to finding brighter perspectives on Southport’s future.

Since my trip to the town, the few Southport stories that have made the national headlines have often been negative or lacking in clear information.

Southport’s historic pier, one the town’s main attractions, closed in mid-December last year. The closure was reported on by the BBC and others, but a clear announcement of what this meant was absent from Sefton Council. Even the operators of the café on the pier posted on Facebook that they were left frustrated at the situation. The pier remains closed and the council has yet to say when it’ll reopen.

Southport Pier, closed. Photo: Ray Woods

Southport Pier, closed. Photo: Ray Woods

There was also news about Southport Pontins holiday park, which as it’s in Ainsdale will leave Southport’s constituency if the boundary changes go ahead. The Home Office were reportedly looking into taking over Pontins as a site to house asylum seekers.

The BBC and the Guardian reported that the Home Office had given up on these plans following objections from Sefton Council. But a few days later, Southport’s MP Damien Moore asked for clarity about the fate of Pontins in the House of Commons. The Minister for Immigration, Robert Jenrick, seemed to suggest the decision was still up in the air and in the hands of Sefton Council. Pontins’ future remains unclear.

For me, these national stories are particularly concerning for places like Southport which rely on tourism. If people think attractions are closed and can’t tell if holiday parks will remain open, they may not come.

I also wonder what confusion over such stories means for communities. Given other issues like the upcoming boundary changes, people in Ainsdale could be forgiven for being very concerned about where they’re going. The Liverpool Echo reported that Joseph Abbot, manager of a bar and grill in Ainsdale, said it “would be a massive worry if Pontins closed. I hope to god it doesn’t.”

These stories will inform what people will think of their future, how they see their political community, and how they engage with their MP and council. These stories will also shape people’s perceptions of the places where they live and where these places are going. This means they’ll likely affect how people talk to institutions like the boundary commission that influence their political future.

As a result, it was important for me to see articles like one by Andrew Brown on InYourArea. It outlined about two dozen developments in Southport, including new supermarkets and a government-approved £73 million events centre.

“I think these are incredibly exciting times for Southport”, Andrew told me. “I think March of last year, Southport gained town deal funding from the government, £37.5 million. That was the second highest of anywhere in the country. The government’s obviously seen potential in Southport to really invest heavily. And they estimate that that £37.5 million is going to attract around £400 million of further private investment.”

And it’s such investment that’s needed in Southport and elsewhere. A report by the IPPR North think tank suggests that public and private investment is low in the UK, coming 35 out of the 38 OECD countries. The North also fares worse than the UK average.

I’d also like to see more investment in communities. But this’ll need their buy-in and participation. The Labour report mentioned greater deliberative processes as one way to do this, highlighting an example in the borough of Newham.

The borough has established a permanent citizen’s assembly. This involves 50 local residents being invited to discuss a topic chosen by the community to create recommendations for the council. However, even if such assemblies were rolled out across the country, local communities and those participating in assemblies would probably benefit if people had better access to local news.

It’s Never Really the End of the Line

Dorothy told me that times do change and you have to accept it. However, I hope that she and other people in Ainsdale and elsewhere won’t feel that such change is happening to their detriment and without them having a proper say in the future.

Southport and Ainsdale’s boundaries may soon change again. This time, the Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) will be involved instead of the Boundary Commission for England. This time, it’s Sefton Council’s boundaries that may change. The process may begin soon.

It’s not possible to say what will happen yet. I asked Greg Myers, a Labour Sefton Council member, about the changes. “It’s still very, very early days”, he told me. “There wouldn’t be much to say on that, because there is literally nothing to say apart from the fact that, yeah, it’ll be under review.”

What is possible to say is that the changes could be significant, again just due to the time that’s passed since the last review. It’s been about two decades.

Lancashire may also soon be changing. According to the Lancashire Telegraph, if Labour wins the next general election, the party would like to see the county gain a devolution deal soon after. The article also suggests the Conservative government will soon talk with Lancashire about devolution.

Who knows what the impact of these developments could be. It’s also difficult to say what changes to the constituencies may mean.

However, John Pugh highlighted one possible consequence for Ainsdale by ending up outside of Southport’s constituency. He suggested Ainsdale may have to be “very lucky” to get any of the town deal investment money for Southport Andrew mentioned. There could also be implications for Ainsdale’s ties with the rest of Southport, particularly if it forms new links with the proposed constituency’s areas in Lancashire.

Ainsdale

Ainsdale

Regardless, given the impact of the local boundary changes in the 1970s, it’s hard to say that the recommended boundary alterations won’t have consequences for the future.

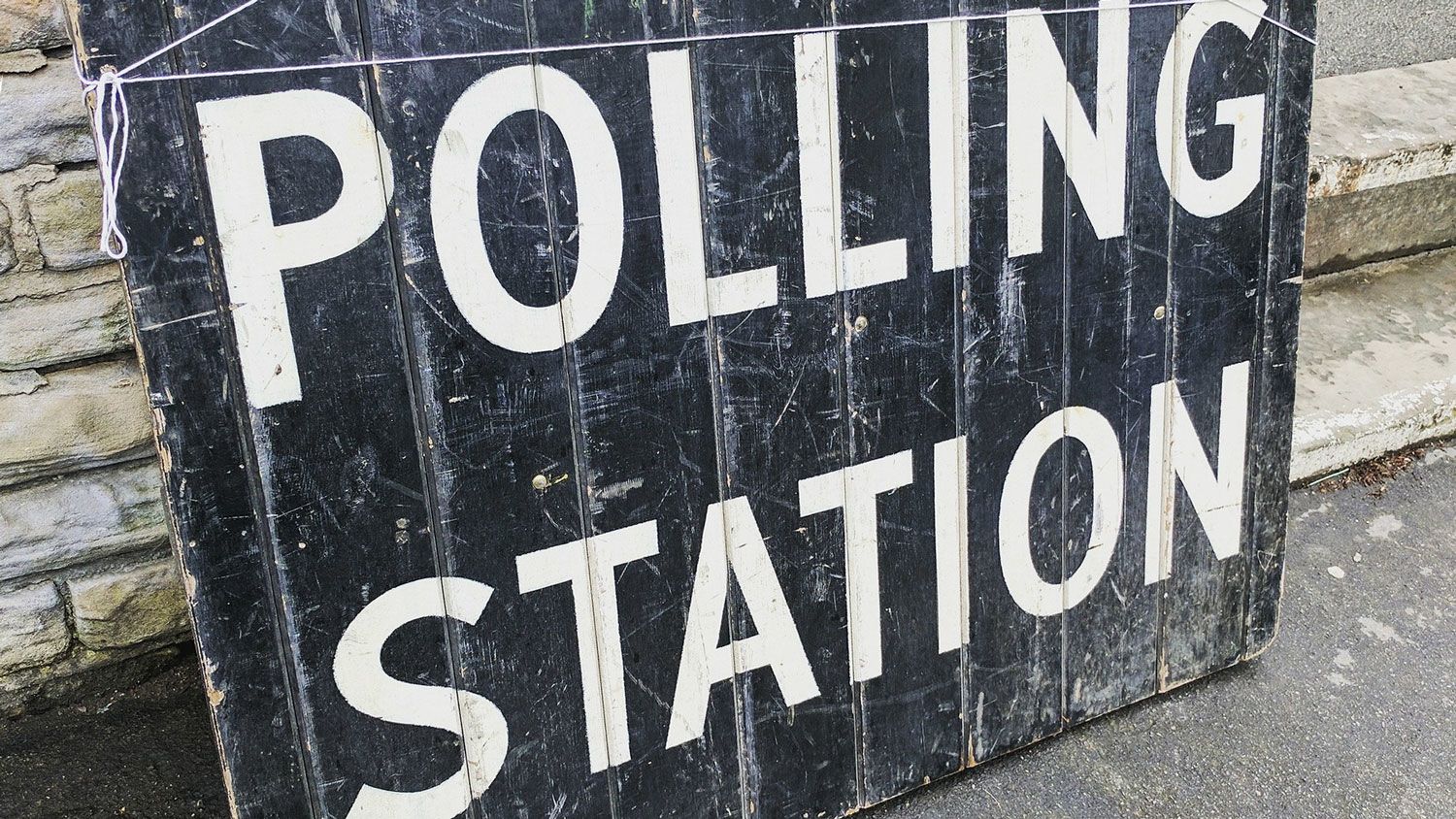

There’s also other changes closer at hand. For instance, there’s the coming requirement for identification to vote at polling stations, including for the local elections in May. Such developments highlight the need for people to have access to information to ensure they can vote.

A Final Story

After returning to my hometown of Southport, I was left concerned that democracy could slip away in certain places. This could even happen without us noticing as people drift into apathy. However, as long as there are people who are interested in local communities and making things work, there’s always a chance that things can turn around and communities can rebuild.

While in Southport, I talked to Joe McNulty from the High Park Project. The project aims to tackle health, social and community issues in High Park, a Southport suburb that Joe told me is within the 10% most deprived areas in the country.

Joe McNulty

Joe McNulty

During the covid pandemic lockdowns, Joe said “there was a wellspring of community spirit” in High Park and people were spending more time in the local area. Joe saw an opportunity to help community members see they can make change happen. He put a bid in to the Liverpool City Region Community Environment fund to get money for planters and trees to improve the area. In the bid, he said the community would help.

“And it kind of worked”, Joe told me. The community helped plan the project and build the planters. A community group was created. Some locals told Joe they didn’t think the planters would last. But they have. “They’ve kind of looked after these planters”, Joe said.

Joe has also started to notice that people’s view of High Park is changing. When growing up, Joe said High Park wasn’t really the sort of place people wanted to be. Joe told me people used to say “you wouldn’t want to buy a house there because it’s High Park”. People would even claim their road wasn’t in the area. But he’s noticed a change. People are identifying with the place and its name. Joe said “people are like, ‘oh, I live in High Park’.”

Names and places matter to people. Perceptions of these can change quickly within a community.

My hope is that whatever the new UK political map looks like, people and communities will find a way to be heard. I also hope that when future boundary recommendations come through, such as for Sefton Council, people will feel sufficiently part of the process to see the changes as their own.

Perhaps people in Southport, Tarleton, Banks, Rufford and the rest of the new constituency will find common cause in feeling that they are not heard. Jonathan told me that as Banks is right on the edge of Lancashire, “we tend to be a little bit forgotten.”

Perhaps these places will also rediscover and celebrate their common history of surrounding the area that once was the largest lake in England. At the very least, there could be common issues related to flooding that may resonate in the future, especially if, as the Met Office suggests, wetter winters are to come.

I was left with a distinct impression from my journey around Southport and the borders proposed by the Boundary Commission for England.

Southport

Southport

You don’t really need to focus on these boundaries. What’s important is the communities that exist within these lines. These are places, if their agency is recognised, that are constantly shaping themselves. This is the case with Joe’s community.

Even with Southport’s current moat-like wall, what counts is what’s within this boundary and how this can split communities as well as bind them together.

The borders given to us will shape our lives and future in many ways we cannot foresee. This means it’s important to ensure these lines reflect the people that live within them. This means communities must have a role to play in forming these boundaries. But to do this, communities need more information, more protections and the ability to be heard.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank those who have helped me with this story. This includes all those who gave their time to be interviewed or answer questions for my project. I’d like to thank my parents for giving me extra insight into the goings on in Southport, including by my Dad driving me around the area. Finally, I’d like to express special thanks to Kevin Bishop, my tutor at Falmouth University, and my partner Nora for their deep and insightful feedback and encouragement throughout the process of crafting this story.