Lines in the Sand: Part 2

Changes to the UK’s political map and implications for the voice of communities.

24 April 2023

Swiss-based freelance journalist

Michael Woods

Photo: Nora Woods

The UK’s political map is under review. The next general election is less than two years away. When it takes place, parliamentary constituencies are likely going to change, some significantly. This is the case in my hometown of Southport, at least in my view. In Southport and elsewhere, the news isn’t reaching everyone and not everyone’s happy about the changes. Are communities being left out in shaping themselves and their future?

This three-part series is the story of my attempt to answer this question. In this second part, I describe what I’ve discovered by exploring local boundary change history and by visiting key locations in and around my hometown.

Transparency note: This project uses generative AI. Click here to find out more.

Another Place? Sefton and Now Liverpool

From the perspective of the Boundary Commission for England, moving Ainsdale ward from Southport into the neighbouring constituency of Sefton Central is not a big deal. This was still the case even after receiving negative feedback on its recommendation for this to be done as part of the 2023 review of parliamentary constituencies.

In the report that addressed such feedback, the commission referred to the recommendation affecting Ainsdale as “minor change”.

“As a consequence of the changes to the existing Southport constituency, the existing Sefton Central constituency, which could have been left wholly unchanged, was instead subject to minor change in the initial proposals: it would include the Ainsdale ward from the existing Southport constituency, and no longer included the Molyneux ward”.

The perspective of many people in Ainsdale is different. As I said in part one, I talked to Dorothy and Eric from Ainsdale about the recommendations. Along with many others, they were concerned about the commission’s proposed changes for the place where they live. Dorothy also told me they’ve had enough changes and that they feel they haven’t been asked about them.

To try and understand what these changes were and what they could mean for those that are coming, I thought I’d look into the recent past. Eric mentioned to me how Southport had once had a choice about joining Lancashire or ending up under Sefton Council. I started here.

Southport was once a county borough. Things get a bit complicated when it comes to local government, at least I think so. But I like B. Keith-Lucas’ description of these former layers of government. He said a county borough was like “an island of self-government in a county, in no way under the jurisdiction of the county council.”

Southport’s time as such an island was ended by a controversial redrawing of England and Wales’s political map involving the Local Government Act 1972. Southport ended up with two new levels of local government: Merseyside County Council and Sefton Council.

The Six Metropolitan Counties

The Local Government Act 1972 created six metropolitan counties in England. Each had two tiers of government, with the upper-tier council covering the county.

Derivative work: Metropolitan Boroughs borders courtesy of Nilfanion. CC BY-SA 3.0. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright

Derivative work: Metropolitan Boroughs borders courtesy of Nilfanion. CC BY-SA 3.0. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright

Margaret Thatcher’s government abolished Merseyside County Council, along with the other metropolitan county councils. This left Southport with Sefton Council.

But given what Eric said in part one about losing out after joining Sefton Council, why didn’t Southport join Lancashire County Council instead?

I asked Dr David Jeffery, a lecturer in British politics at the University of Liverpool. He thinks it was ultimately a numbers game. He told me “the government really wanted minimum numbers in each local authority, without them being too big”. In Sefton Council’s case, he said Southport was needed to boost the council’s population and tax income.

Local opinion didn’t matter too much for these changes. Dr Jeffery told me factors like population sizes and other things came first. Things haven’t really changed either.

Metropolitan Borough of Sefton

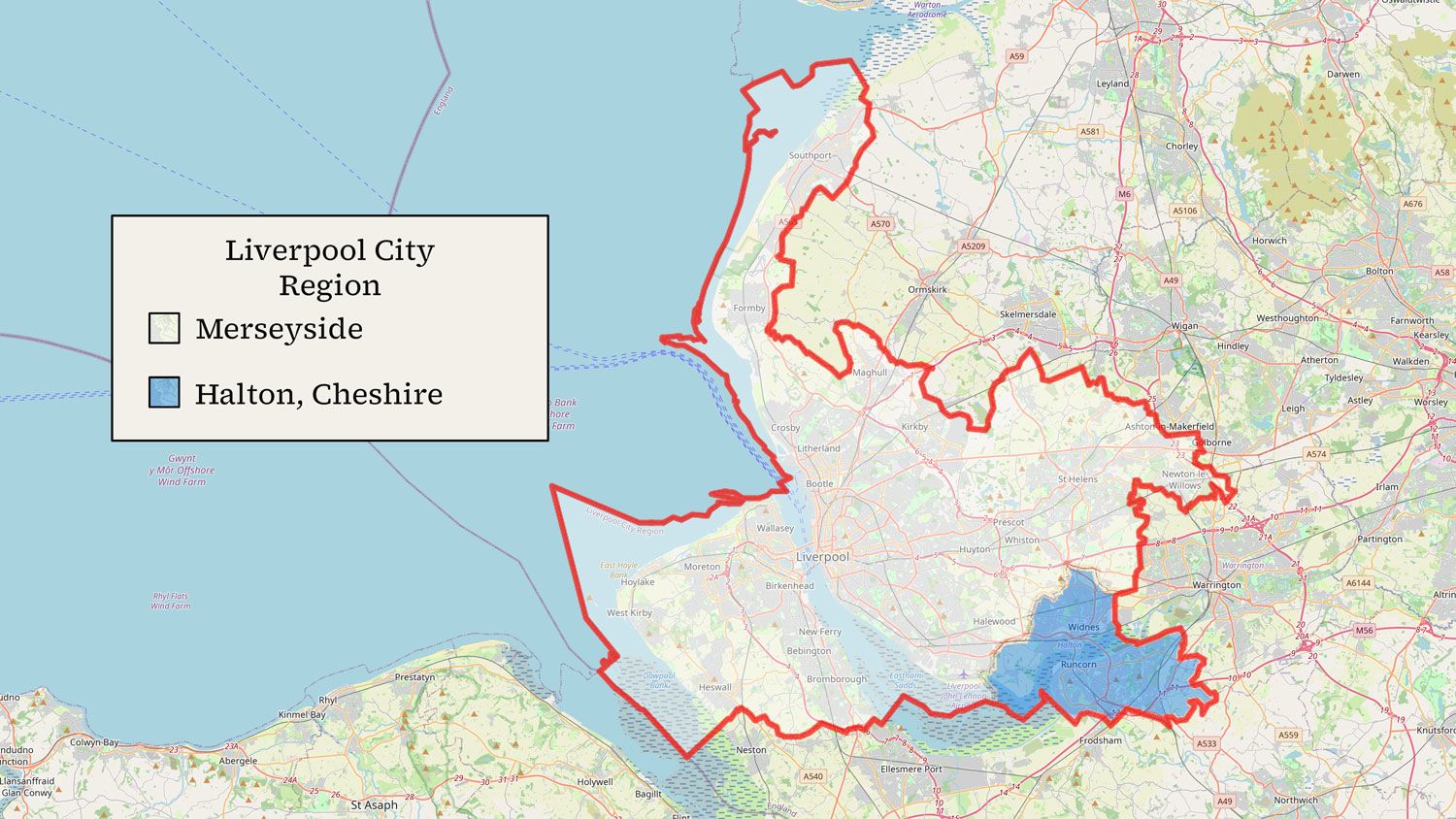

In 2014, Sefton Council became part of the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority. This region consists of Merseyside, including Southport, and the Borough of Halton in Cheshire. Since being created, the combined authority has gained powers over transport, finance, housing, employment and more. In 2016, a mayor was created for the region.

Other areas in England, like Manchester and South Yorkshire, have also gained combined authorities. However, Dr Jeffery writes that these were established through “an elite-driven process, lacking any meaningful public engagement or support”.

The process was not democratic. In fact, Dr Jeffery told me “that local government has long been a plaything of central government”.

But perhaps not talking to communities when overhauling local government can drive a greater wedge between local areas. I’ll use Southport as an example.

Liverpool City Region

Divisions existed before Merseyside’s creation in the 1970s, but some evidence suggests this widened the gap. Dr Helen West at the University of Chester says that Merseyside’s formation strengthened Southport’s identity, increasing the view among its residents that they’re different from people in Liverpool. In fact, her research suggests that this perception was strong enough to affect the town’s accent.

Since the 1980s, each MP elected to the Southport constituency has also advocated for Southport to leave Sefton Council. Damien Moore, Southport’s current MP, lists this goal as a core campaign issue.

All this seems to support what Dorothy said. There have been changes affecting Southport and communities haven’t had a real say on them. The response to these changes also illustrates that these boundaries mean something to people and that altering them has lasting effects. They’re not minor arbitrary lines.

Things Get Confusing

With all this in my mind, I could understand Dorothy and Eric’s frustrations. Things didn’t end there. To better understand what the Liverpool City Region meant for Southport, I looked at Liverpool.

It turned out that the local political map for Liverpool City Council has been completely redrawn. This has been done by the Local Government Boundary Commission for England, not to be confused with the Boundary Commission for England which deals with parliamentary constituencies. The existing map for Liverpool has 30 wards. The new one will have 64.

These new wards will be used for local elections in May. This means Liverpool’s 64 new wards will be in use before the Boundary Commission for England even hands in its final recommendations for parliamentary constituencies in July.

Liverpool. Photo: timajo/Pixabay

Liverpool. Photo: timajo/Pixabay

The Boundary Commission for England takes wards seriously. In its 2023 parliamentary review guide, the commission says wards are “well-defined and well-understood units”. In fact, it describes wards as its “default building block for constituencies.”

However, the commission won’t consider Liverpool’s new wards this time. As they told me, effectively they can’t.

“As we have to base our recommendations on a fixed date, for the 2023 Review of Parliamentary constituencies we use local government boundaries as existing or prospective on 1 December 2020.”

This is set out in legislation and it’s not up to the boundary commission. Liverpool’s new boundaries only reached a prospective stage last year.

In a way, this is unfortunate. It means the commission can’t consider these new wards when they’re thinking about how to redraw the map and maintain local ties in the region, including in Southport. The commission even says it had to recommend “fairly significant changes” for Liverpool’s constituencies given the large voter population size of the city’s existing wards. But just to mention this again, these wards soon won’t exist.

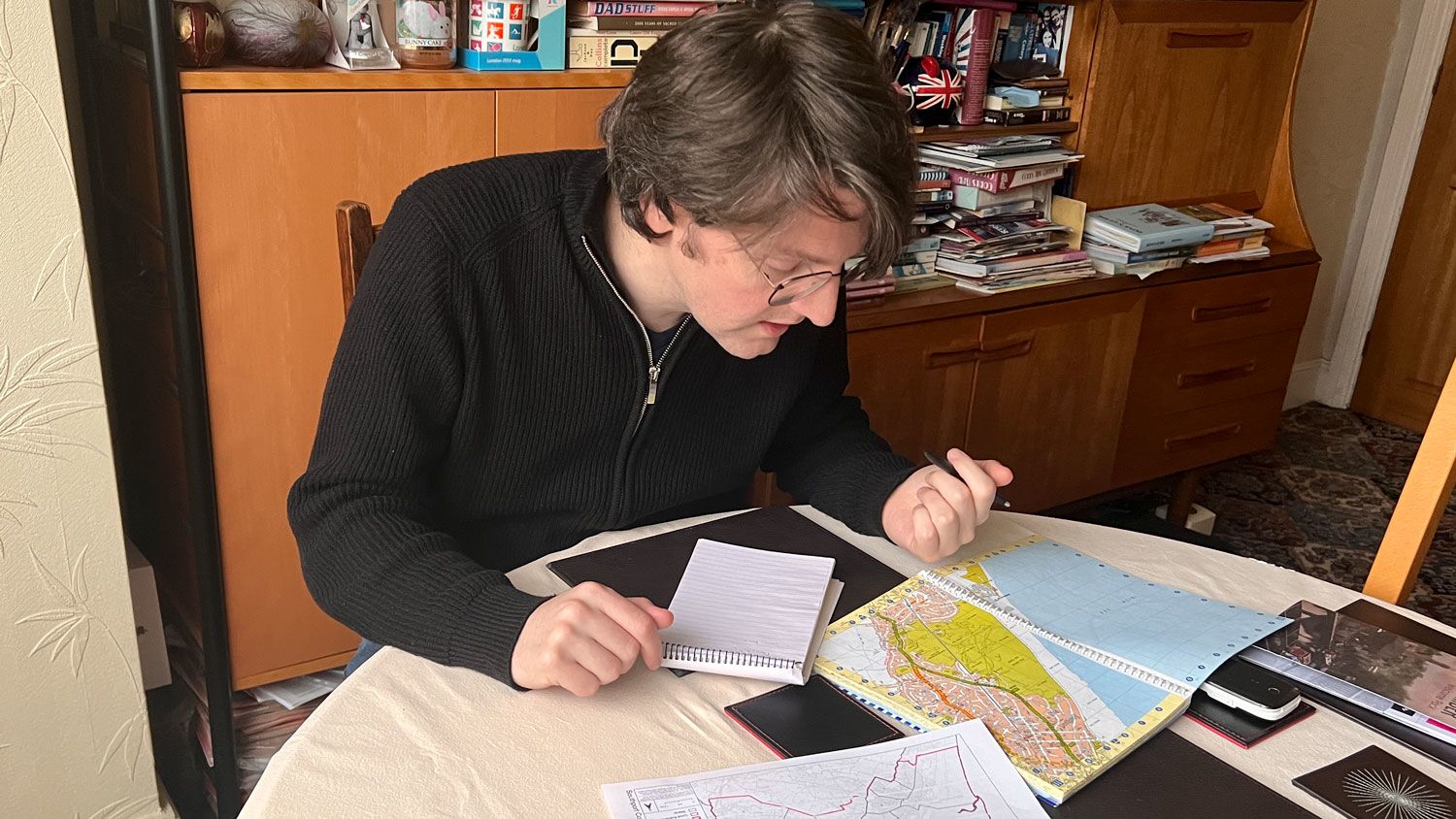

Photo: Ray Woods

Photo: Ray Woods

There’s more I found difficult to understand.

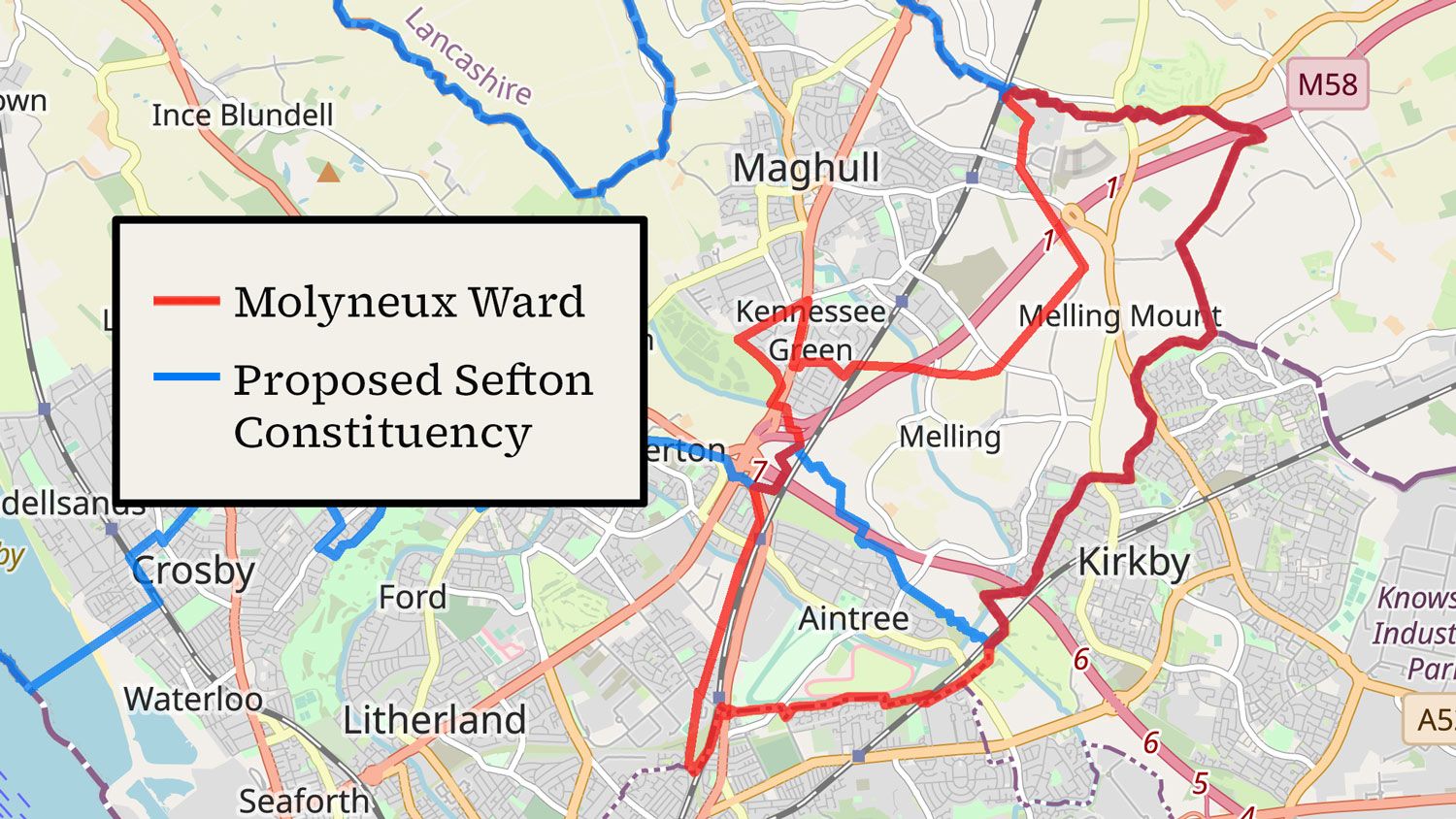

The boundary commission have changed their proposals for Sefton Central, Southport’s neighbour. Initially, the commission suggested moving the whole of Molyneux ward out of Sefton Central and into a neighboring Liverpool constituency. Now the commission recommends splitting the ward. In this updated suggestion, only Aintree, home to the Grand National horserace, will move.

The commission explain they think this ward can be split given their assessment of geography, history and local ties.

However, I could only find three or four public comments that put forward this split on the commission’s site. Over 20 directly opposed Aintree’s move, and it will still be transferred. This recommendation didn’t seem to match up with the commission’s point about wards being key constituency building blocks. Nor did it seem to reflect strong local sentiment.

Molyneux Ward

I don’t envy the difficult situation facing the boundary commission. Redrawing these lines is no easy task. But I couldn’t understand what was going on either.

It’s true the boundary commission seeks people’s views during the review process. However, it was unclear to me how these comments influenced the commission’s decisions. I was also unsure if people could effectively air their opinions when it’s so difficult to make sense of what’s going on.

That this is the case is shown by some of the comments for Southport on the commission’s website. Instead of giving feedback on the suggestions, some comments just ask for information.

“Does Southport stay in Sefton if these changes come about?”

“I can understand the need to change some of the boundaries, but there is no real detail about what these changes actually mean in practice. Are new councils being created? Will policing areas change (will Southport become part of Lancashire again)?”

These two examples show some people from Southport were clearly unsure what the recommendations meant for the town, including its local ties with Sefton Council and Lancashire.

Southport won’t leave Sefton Council as a direct result of the 2023 review. However, I still wanted to get a better grasp of what the suggested changes could mean for this link and other ties. I decided I had to visit some of the areas in and around my hometown that would be most affected by the new boundaries.

Boundary Crossings

I haven’t driven in the UK for about a decade. I didn’t fancy taking the bus. So I asked my dad, who lives in Southport, if we could go on a short road trip around my old hometown.

Dad and me on the pier.

Dad and me on the pier.

Ainsdale

We started off by driving down to Ainsdale. It was a fairly sunny day, and the air was about as still as it gets in November, meaning my mic was filled with wind noise wherever we went. My dad’s hearing aid also picks up all the wind. At times, it was difficult to talk.

We drove down to where the proposed boundary for Southport will be. It seemed an odd site for a new division to me. The only dividing line seems to be the road.

Windy Harbour Lane, where the new boundary will run down the middle of the road.

Windy Harbour Lane, where the new boundary will run down the middle of the road.

I took a few pictures of the streets that’ll be split.

At the end of one is Southport and Ainsdale Golf Club. Golf’s important in Southport. The town’s tourist page claims Southport is England’s golfing capital. Through the club’s gates, I could see a few golfers making their way around the green. The changes will see the club end up in Sefton Central.

Birkdale High is also on the Ainsdale side of the road. This means the school will be split from the rest of the Southport constituency, including Birkdale.

The entrance to Birkdale High School. Gates to Southport and Ainsdale Golf Club in the background.

The entrance to Birkdale High School. Gates to Southport and Ainsdale Golf Club in the background.

On the other side of a main road, heading inland, is Carr Lane. The new border will run down the middle of this road too, but again there’s no obvious other split.

I thought there was one, though, when I walked past a line of houses. The land opens up into Lancashire. Out there, there’s fields. The change is stark, from an urban to a rural area. This division makes Southport feel like a medieval town, with a wall of houses on its outer rim and a moat formed by dykes, sluices and rivers.

From a map, it can look like Southport has open green spaces for fields. But most of this is just dunes, parks or golf courses.

We drove down to Ainsdale’s small and tidy centre. Like the rest of Southport, Ainsdale features Merseytravel yellow bus stops and train signs. The aquamarine colours of the Arriva buses were a common sight. The ties to Merseyside are visible.

The place was fairly quiet. A few locals were going about their business.

After watching a few trains go by at Ainsdale station, we headed down to the village’s beach. It was blustery. Here there’s a large mural on an abandoned building that’s surrounded by fences and barriers. There’s also Southport Pontins, a holiday park. Pontins looked empty.

We clambered over a few sand dunes. I made my usual effort to walk out to the sea. The land here is flat. Locals often joke the tide never comes in. The sea was too far out for me this time too.

Somewhere in the sand, a new invisible line will soon stretch out to the sea.

From the beach, you can see Blackpool and the Lake District to the north. To the south, the Welsh mountains.

There’s a gas rig out at sea and windmills. But it’s all rather distant. The sand was strewn with shells from cockles and razor clams.

Back in the car, we headed down to the current boundary. I was surprised how evident the existing split is. The current Southport constituency ends with a break created by a Royal Air Force training station, dunes and another golf club.

Just beyond the current Southport constituency boundary, looking towards Formby.

Just beyond the current Southport constituency boundary, looking towards Formby.

Southport’s Northern Border

We drove along Southport’s front, passing sand dunes and a string of white vans on the beach belonging to people picking cockles. In north of the town, estates are popping up. It’s around here that the Sefton and Merseytravel signs come to an end.

Part of the boundary is created by the Three Pools Waterway, a section of a water drainage system which acts like Southport’s north-eastern moat. This ends at a mid-twentieth century pumping station, which sends water and the border out to the sands and the Irish Sea.

Border at the pumping station.

Border at the pumping station.

Lancashire

Beyond the Three Pools Waterway is Lancashire and the village of Banks. Beyond Banks, there’s fields and farms. The agricultural land around here is classed as excellent and among the best in the country.

All this area will come into Southport’s constituency if the commission’s recommendations go through.

In Southport, you hardly see a tractor. Out here, they’re everywhere. This has likely led to another suggested change for the Southport constituency. It’ll stop being a borough constituency, which generally represent urban areas, and become a county constituency, which represent rural areas.

Out in the fields, there’s also an old division. It lies between Southport and the villages of Tarleton, Hesketh Bank and Rufford which may soon join the town’s constituency. These two areas were part of separate hundreds, referring to an ancient level of English local government which predates the Norman Conquest. The land Southport now sits on was part of the Hundred of West Derby. This stretched down to Liverpool. Tarleton, Hesketh Bank and Rufford were part of Leyland. According to Visions of Britain, hundreds once had “administrative and judical functions”, but these faded in the 19th century.

As we travelled through the countryside, there wasn’t too much to see. A few villages, people tending fields, a scattering of caravan parks. The flat landscape is otherwise dominated by fields and large agricultural greenhouses.

The old geography of the area explains all this. Local historians say that until around the end of the 17th century, the area was divided by Martin Mere, the largest lake in England. They also suggest that even after being drained, this mere returned after flooding, reappearing as late as the 1950s.

Extent of the Area Covered by Water around Martin Mere in Winter 1848 and the Map Today

Click on the white ball below to move the slider.

Satellite Image: Courtesy NASA’s Earth Observatory. Map Image: The Birds of Lancashire, courtesy Internet Archive/Smithsonian Libraries. Photo slider: Flourish team.

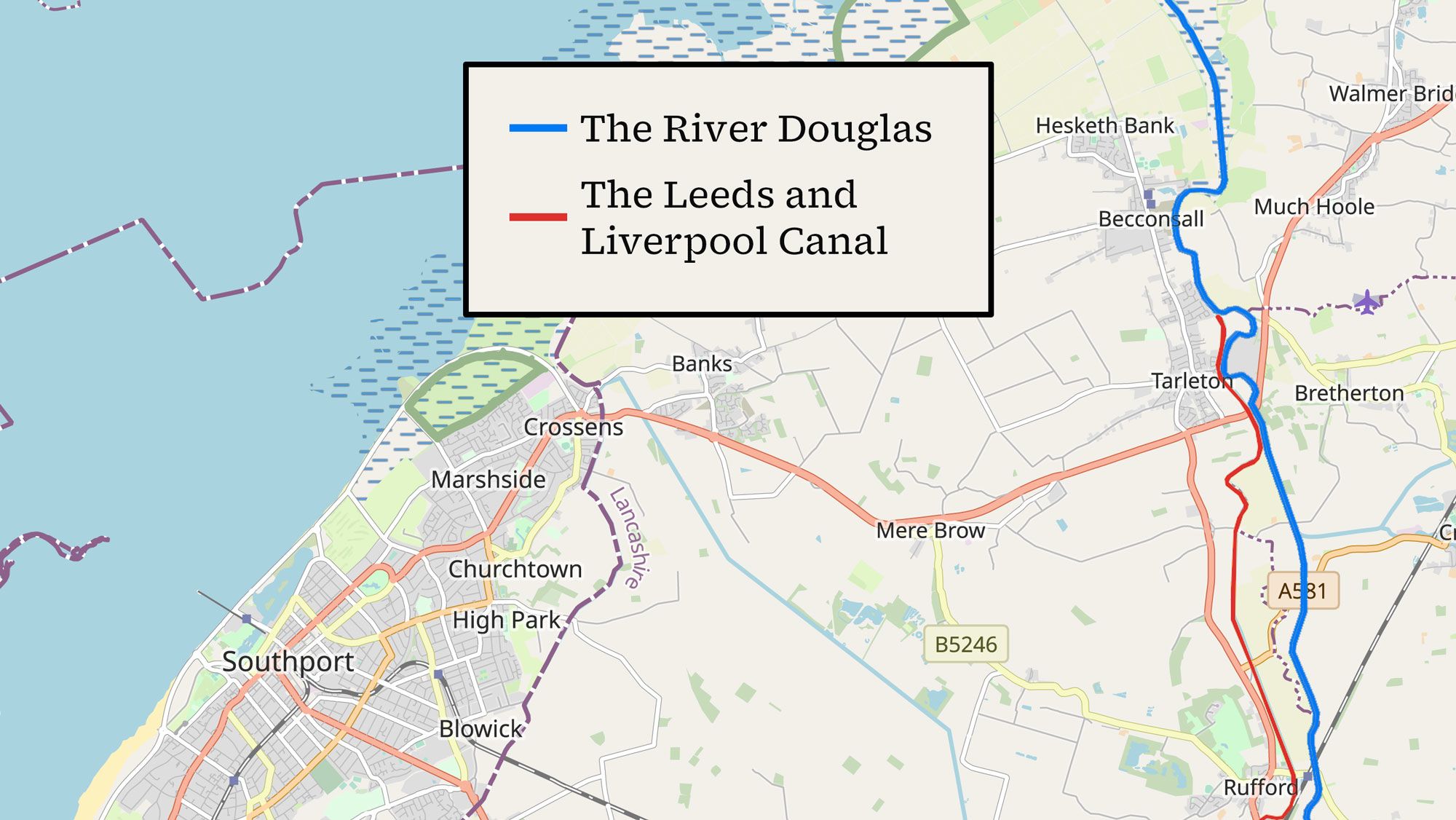

Martin Mere’s legacy is still important. It’s the lake’s basin that creates the rich agricultural land that’s a key part of the economy for Tarleton, Hesketh Bank and Rufford. Waterways including the River Douglas to the east may seem like obvious boundaries on the map today, but history and geography suggest otherwise.

River Douglas and the Leeds and Liverpool Canal

Rufford is small. I don’t know much about the three villages of Tarleton, Hesketh Bank and Rufford. I do remember Rufford Old Hall from my childhood. Several family trips to the timber-framed National Trust Tudor house made sure of that. In Rufford itself, there’s a pub, a gun shop, a primary school. It wasn’t long before we saw a tractor.

Nearby, there’s clusters of narrowboats moored in a marina just off the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. Smoke was rising from the boats. There’s a small pretty church, where I managed to get splashed by a passing car.

There’s a gap between Rufford and Tarleton. Between them only scattered buildings, abandoned farm houses and the hamlet of Sollom.

We stopped near Tarleton’s Cock and Bottle, a pub with its own bus stop. Unlike Southport, Tarleton has few empty shop windows. There’s a fire station, a football club, a cricket club. There’s also a secondary school, the students of which were piling out as we were passing by.

But what really defines a sense of place?

At the traffic lights in Tarleton’s centre, we could smell the wet earth from the farms around. Tractors drove through the village here too.

Tractors in Tarleton

Tractors in Tarleton

One of the most prominent buildings remains the village church, Holy Trinity. There’s a welcome sign to come in. My dad noticed that the diocese for this Church of England place of worship is Blackburn. It’s the same for Rufford and Hesketh Bank. Southport’s diocese is Liverpool. Just another little difference.

The daylight was starting to fade as we reached Hesketh Bank. It was difficult to tell where Tarleton ended and Hesketh Bank began. But this village ends in the open fields that reach out into the River Ribble Estuary. More productive black soil.

Eventually, we found our way down to the River Douglas, the Southport constituency’s possible new border.

River Douglas

River Douglas

All three villages, and the places in between, seem to hug the River Douglas to lesser and greater degrees. They also seem to look towards Preston, inland and away from the sea. This area doesn’t really feel like a costal area or tourist resort, like Southport and Ainsdale. This left me wondering if local differences affect the work of MPs.

I asked Southport’s former MP John Pugh. He told me “there are certain issues where, in a sense, it doesn’t matter” as they can can appear anywhere.

However, John pointed out it can be important. He gave the examples of access to local hospitals, local school issues and town centre regeneration, each of which “only really matters to people in given communities”.

John also said that the more varied a constituency is, the harder it can be for an MP to represent constituents. “I think building constituencies around community helps to give a focus to MPs work and the kind of things they campaign for.”

Links and Divisions

So what else defines community boundaries? What else does history say?

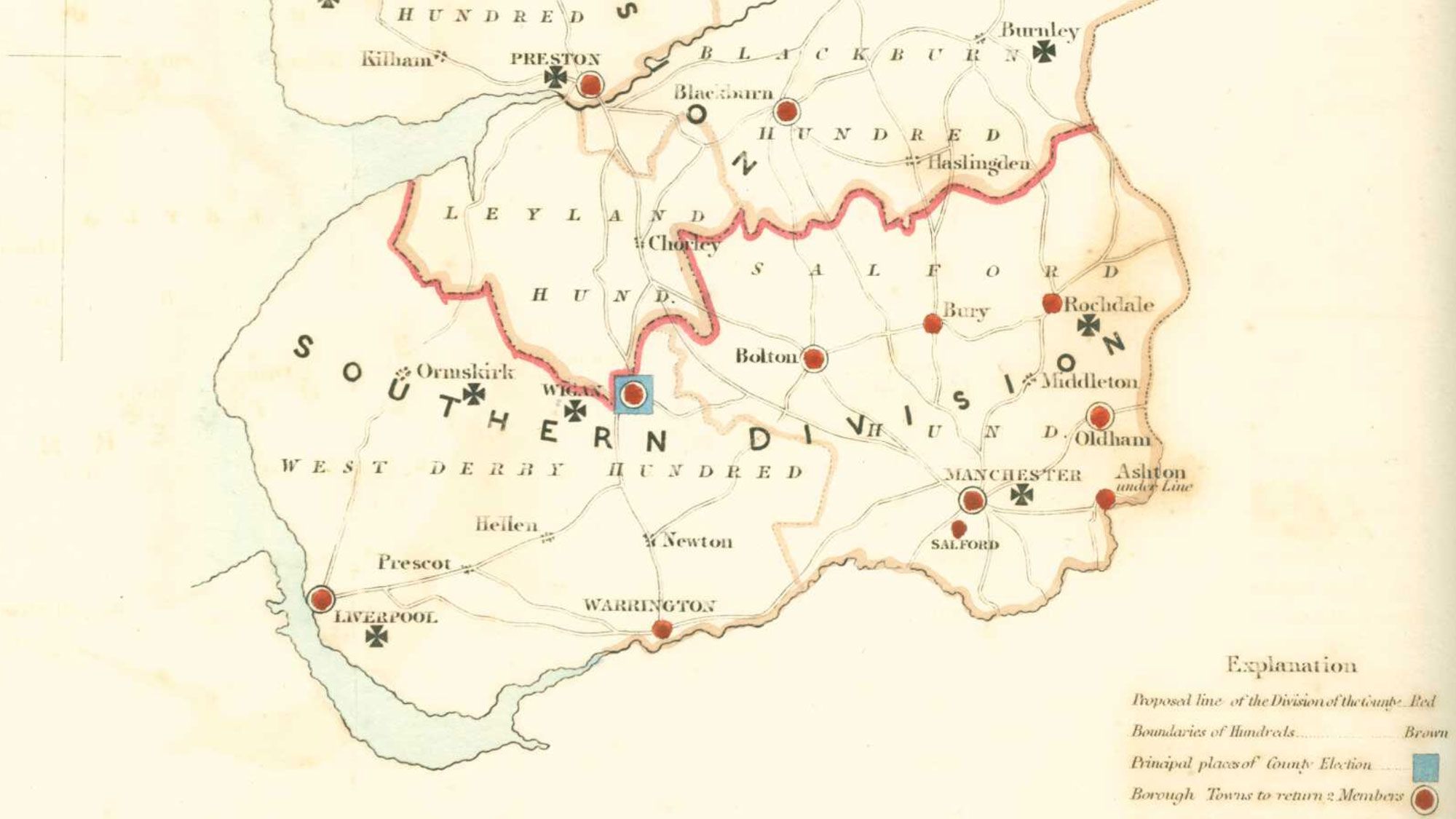

Tarleton, Hesketh Bank and Rufford haven’t been in the same parliamentary constituency as Southport since 1832.

1832 Boundary Commission Report Map of Proposals for Lancashire.

Image: Courtesy of Great Britain Historical GIS. CC BY 4.0. Modified: Cropped.

Image: Courtesy of Great Britain Historical GIS. CC BY 4.0. Modified: Cropped.

Before this, Southport and the three villages were essentially part of the same large constituency of Lancashire. But this also included underrepresented urban areas as far away as Manchester. This split was brought about by the Reform Act of 1832. Parliamentary reform, including issues dealing with reviewing boundaries and constituencies, was a major issue at the time.

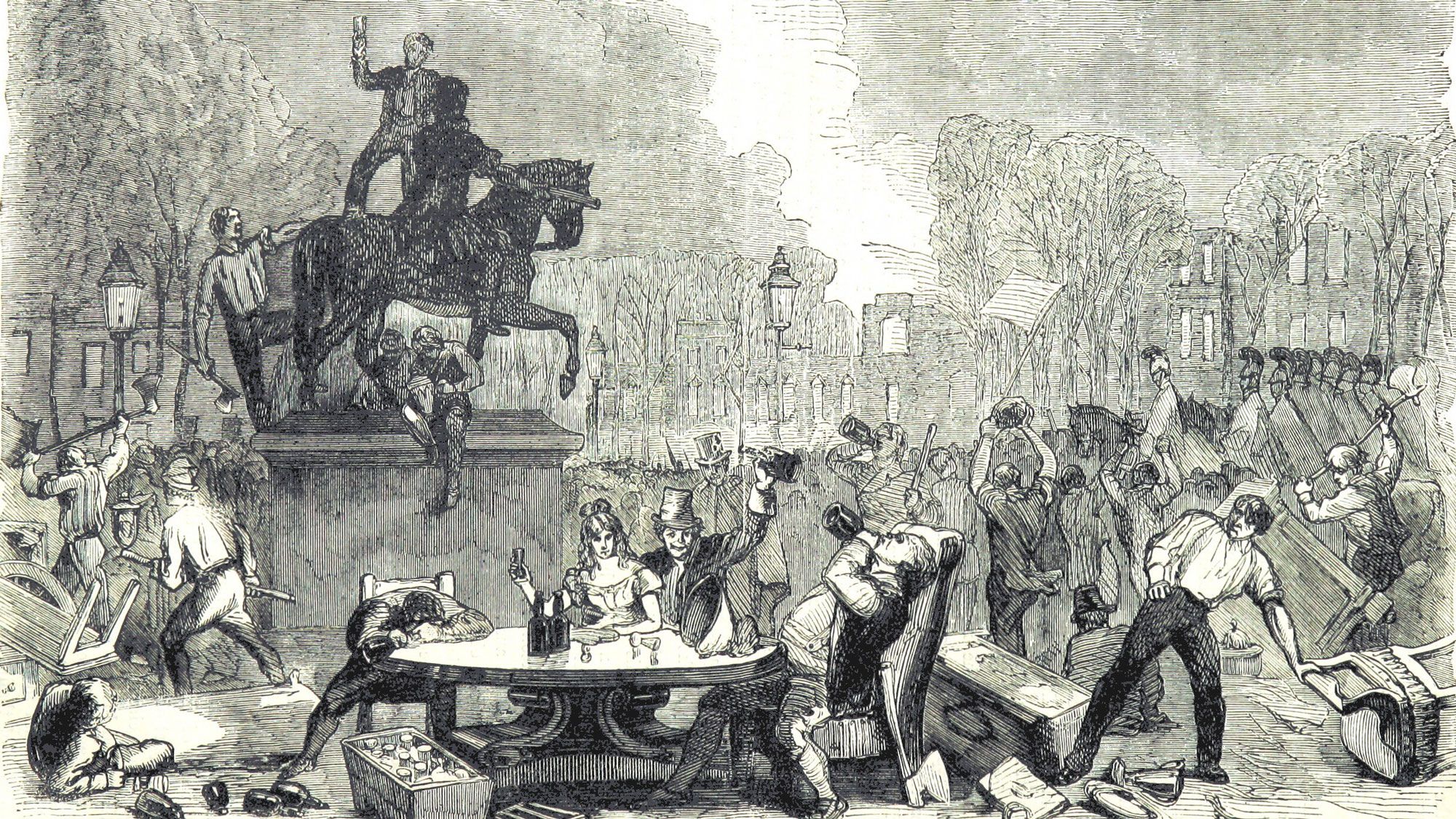

Riots spread across the country when earlier reform efforts failed. Protesters even took over Bristol for two days. Things seem a little quieter today on reform.

The Bristol Reform Riots, 1831. From John Cassell’s Illustrated History of England. Image: Public domain.

The Bristol Reform Riots, 1831. From John Cassell’s Illustrated History of England. Image: Public domain.

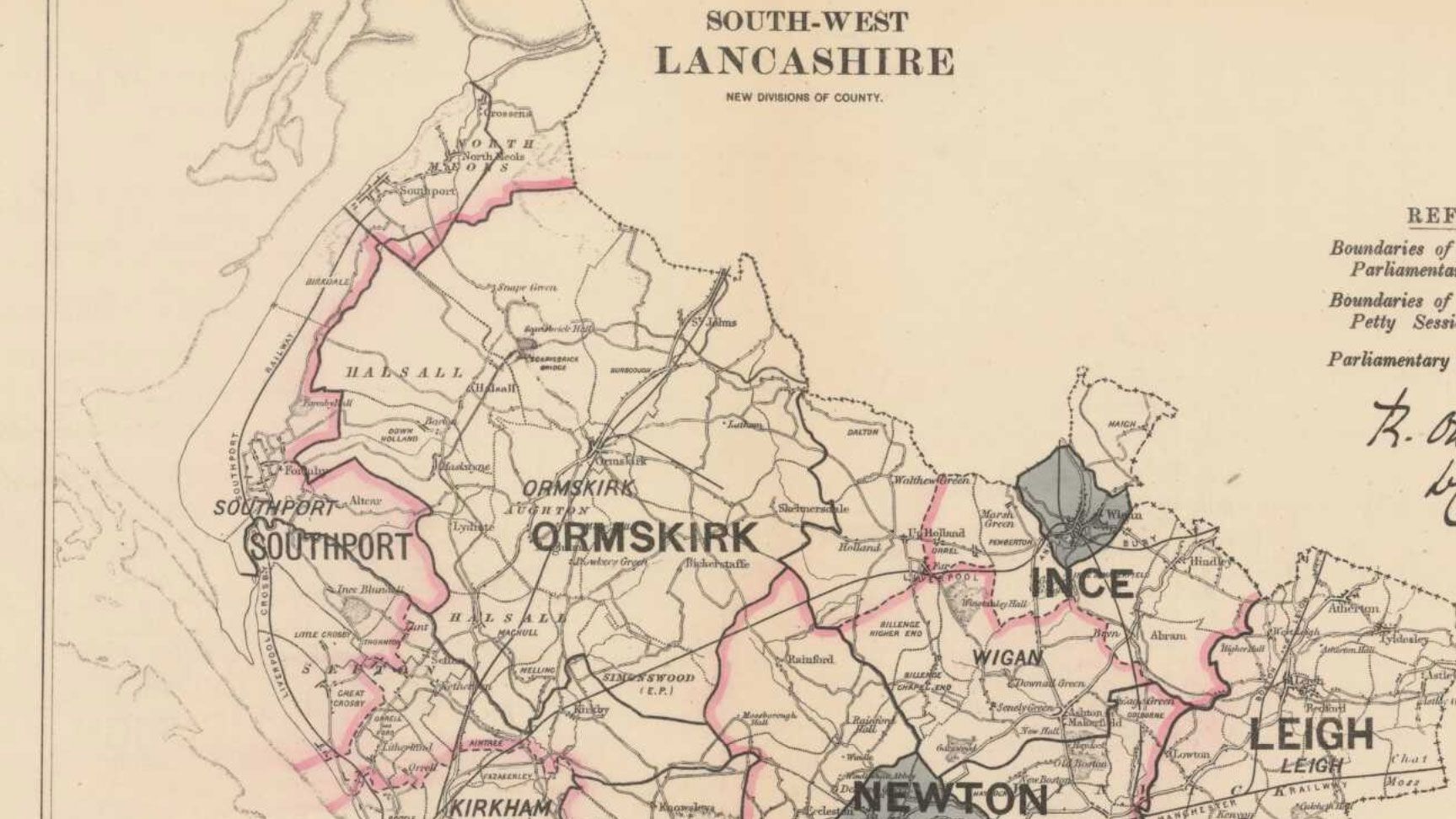

In 1885, another reform act was passed. According to the House of Commons Library, for the first time, there was a goal to make the seats in the UK have similar voter populations. Southport’s constituency was created at this time. Tarleton, Hesketh Bank and Rufford became part of the Chorley constituency.

The Boundary Commission for England does look to history when redrawing the political map. This is shown by their explanation about splitting Molyneux ward above. What’s perhaps important here is that Ainsdale seems to have always been part of the same constituency as Southport, as Dorothy said. In fact, the Southport constituency has changed little since 1918.

1885 Boundary Commission Report Map for South-West Lancashire.

Image: Courtesy of Great Britain Historical GIS. CC BY 4.0. Modified: Cropped.

Image: Courtesy of Great Britain Historical GIS. CC BY 4.0. Modified: Cropped.

Then there’s the other levels of government. It seems difficult to argue that these aren’t important for constituencies given the weight the commission gives wards.

Southport became a municipal borough in the 1860s, absorbing Birkdale and Ainsdale in 1912. In 1905, Southport became a county borough, independent of the county of Lancashire. The three villages became part of the West Lancashire district within Lancashire.

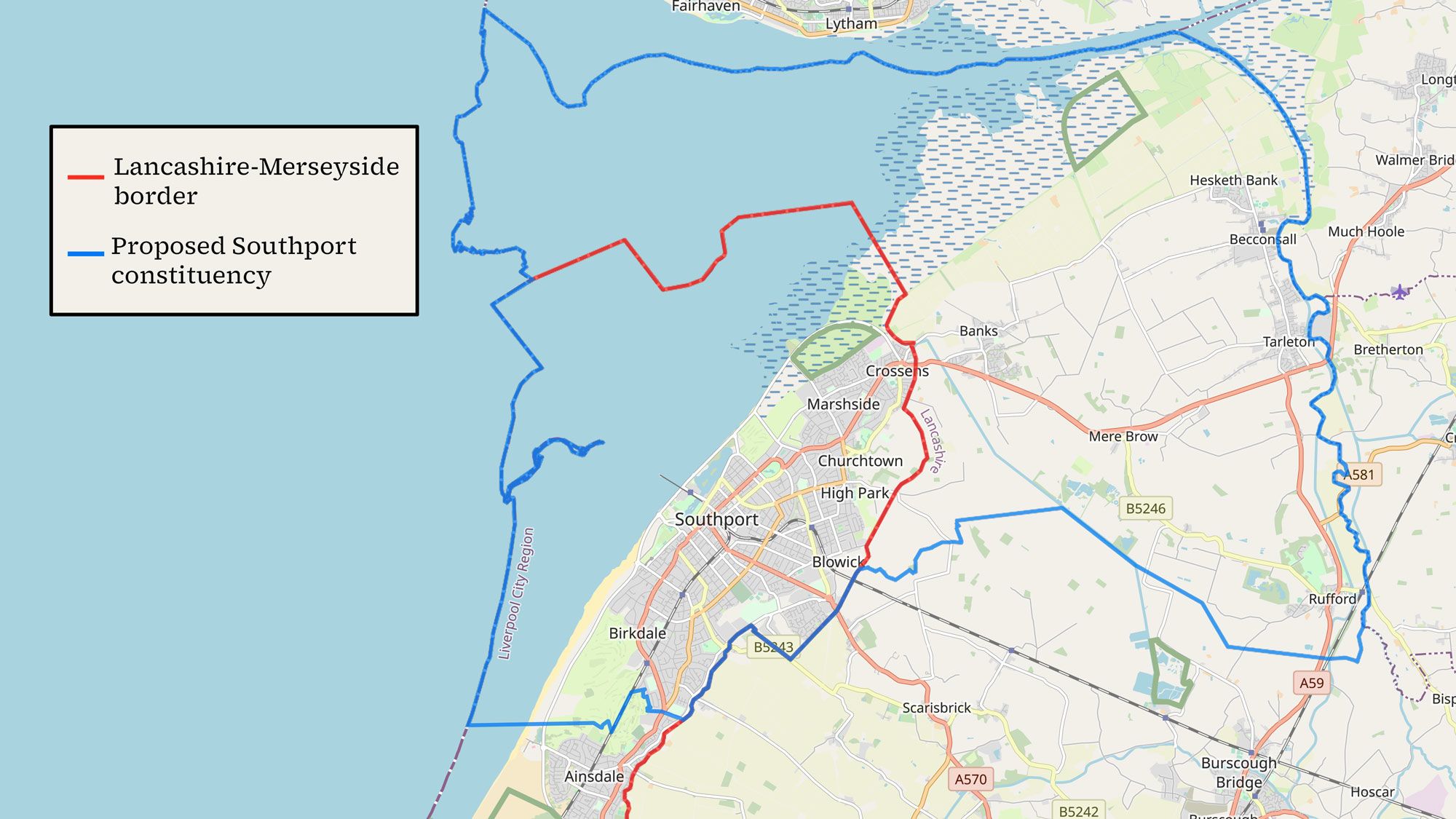

There were other local boundary changes, including those involving the creation of Merseyside mentioned above. But returning to the situation today, it’s interesting to see that the two halves of Southport’s new constituency will be covered by different fire and rescue services, police forces, education authorities and more. These are split by the border between Merseyside and Lancashire. Given the longstanding separation between these areas, this also hardly seems surprising.

All these things give a sense of place and may help tie people to their community. Overall, Southport and the three villages do not seem particularly tied to one another.

County Border and Proposed Constituency

Even those who support the changes sometimes reflect this position. George Rear, the Conservative Party’s campaign manager for Lancashire, spoke at the commission’s public consultations in early 2022. He supported the changes for Southport as they keep Tarleton, Hesketh Bank and Rufford together.

However, Rear also said he wanted the name of the constituency to change to Southport and Douglas. This was to show that “it is a constituency of two halves – the town of Southport and then the rural outlying villages.”

The commission didn’t agree the name change was needed. Still, any MP serving the new Southport constituency will need to consider how to address the needs of both places.

The proposed changes obviously don’t preserve ties in Southport. Given the numerous changes to constituencies across the North West, it’s also not so easy to understand how changing Southport’s constituency helps preserve ties elsewhere. Perhaps it does. Still, the splitting of Southport’s existing constituency and the joining of the two places in its proposed one seem to me to come down to the requirements of a number: the 5% rule outlined in part one. But this is a number possibly just arbitrarily decided upon over a decade ago.

As local opinion appears secondary, it seems important for it to be well informed so communities can speak up when needed.

On this, George Rear mentioned something else that caught my attention. He said some people in Rufford wanted the village to stay in West Lancashire. He thought they were just confused. Rufford isn’t in the West Lancashire constituency. It’s in the West Lancashire council area. Just like in Southport, people in Rufford were unsure what the parliamentary constituency review meant for their local boundaries.

The themes of confusion and insufficient information kept reappearing.

Most people I’d asked in Southport didn’t even know about the suggested changes for the town.

Why was information so lacking?

I continue my exploration of the voice of local communities in shaping their political boundaries in part three. Next time, I look at whether a decline in local media can help explain why people aren’t getting the information they need. I also explore what the future might hold for Southport and communities seeking to shape themselves.

To find out about this project’s other activities, please visit my website here. You can also find useful links for resources on UK political boundary changes and local news here.