Lines in the Sand: Part 1

Changes to the UK’s political map and implications for the voice of communities.

21 April 2023

Swiss-based freelance journalist

Michael Woods

Photo: Nora Woods

The UK’s political map is under review. The next general election is less than two years away. When it takes place, parliamentary constituencies are likely going to change, some significantly. This is the case in my hometown of Southport, at least in my view. In Southport and elsewhere, the news isn’t reaching everyone and not everyone’s happy with the changes. Are communities being left out in shaping themselves and their future?

This three-part series is the story of my attempt to answer this question. In this first part, I recount what I’ve discovered about why the changes are happening and the response to the review in my hometown.

Transparency note: This project uses generative AI. Click here to find out more.

Breaking Old Ground

What is the place where you live? Where does it begin? Where does it end? Do you have a say in this place? Do you feel your voice is heard? I hope so.

I’m not sure if people’s voices are always being heard in my hometown. At least, not when it comes to deciding what the place is, what’s included within it or where its boundaries lie. I’ve come to this view after journeying back to where I grew up to hear what people think about suggested changes to the town’s parliamentary boundaries. This journey has also left me concerned about something: Is there a wider growing problem facing the health of our democracy linked to how we communicate, particularly at the local level?

Concerns about threats to democracy appear to be growing. A recent NPR, PBS Newshour and Marist poll found that 83% of people in the US “think there is a serious threat” to democracy in the country. A report by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance says “half of the world’s democracies are in retreat.” The UK government has created the Defending Democracy Taskforce in response to the threat posed to democracy by foreign actors. But as we tackle these grand and global threats, perhaps we also need to remember the local level to make sure that the democratic ground does not shift away under our feet.

Let me step back. In the spring of 2022, I came across the news on Twitter that the Boundary Commission for England, or BCE, was reviewing parliamentary constituencies.

I moved to Switzerland over a decade ago, but I still feel tied to my hometown, the seaside resort of Southport. My parents live there. So do friends. When I have voted in a general election as a Brit abroad, this is where my vote has been cast. So I was curious.

When I looked at the suggested changes for Southport, I was surprised. A chunk of Southport, Ainsdale ward, was being removed from the town’s parliamentary constituency. A neighbouring area in Lancashire was being added. To me, this seemed odd. My sister’s husband grew up in Ainsdale, as did several of my good friends. I’d always thought of Ainsdale as just another part of my hometown. I have few links to the areas being added.

Had community ties changed? I wanted to know what the local population was thinking. Luckily for me, I didn’t have to search far for answers. The online map that shows the suggested constituencies also features comments from the public.

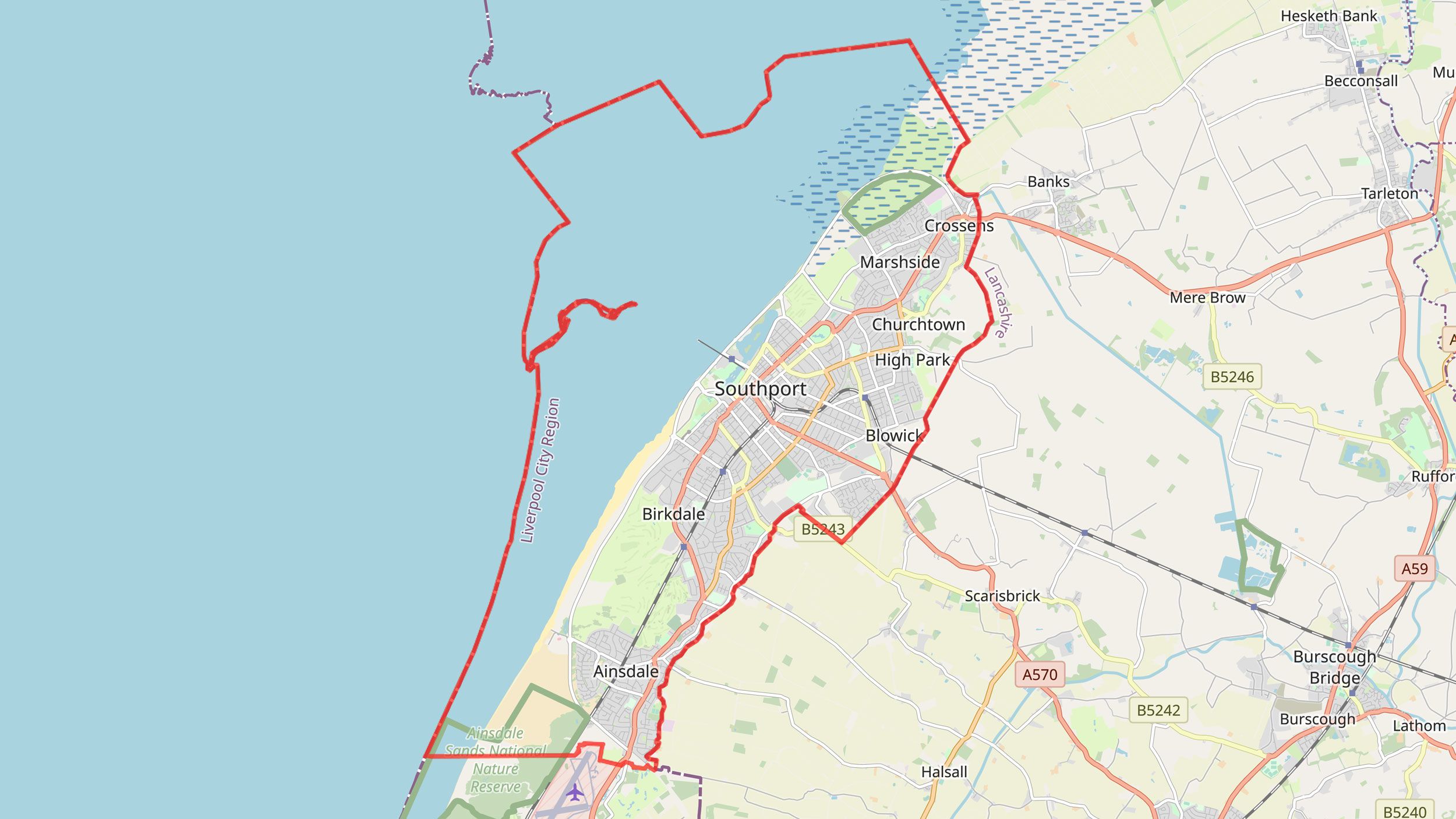

Southport’s Current Constituency

Proposed Boundary for Southport

When I looked, there were 136 comments linked to Ainsdale ward on this online map. Only two of these comments favoured the changes. Three comments were duplications. The rest opposed the proposals, suggesting clear opposition.

Ainsdale is also one of the most commented upon places in England regarding the changes.

All of the public comments are split into England’s wards or electoral divisions, the geographic areas used for the election of local councillors. The BCE says it uses these areas “as the basic building block for designing constituencies.” There are 4,282 wards listed in the BCE data on public comments. When it comes to ranking which places received the most comments, Ainsdale ward comes in at 45.

A brief glance at the comments suggested that some people were clearly upset and concerned.

“It feels like you’re trying to take away my identity!”

“I strongly object to being removed from the Southport constituency and being dragged into Sefton, our voice is effectively silenced in local government already with Sefton council. Not having any real choice of our MP is wholly unacceptable.”

“If this had been more publicly known I am sure the result would be overwhelmingly rejected. Talk to the residents involved.

LEAVE AINSDALE IN SOUTHPORT”.

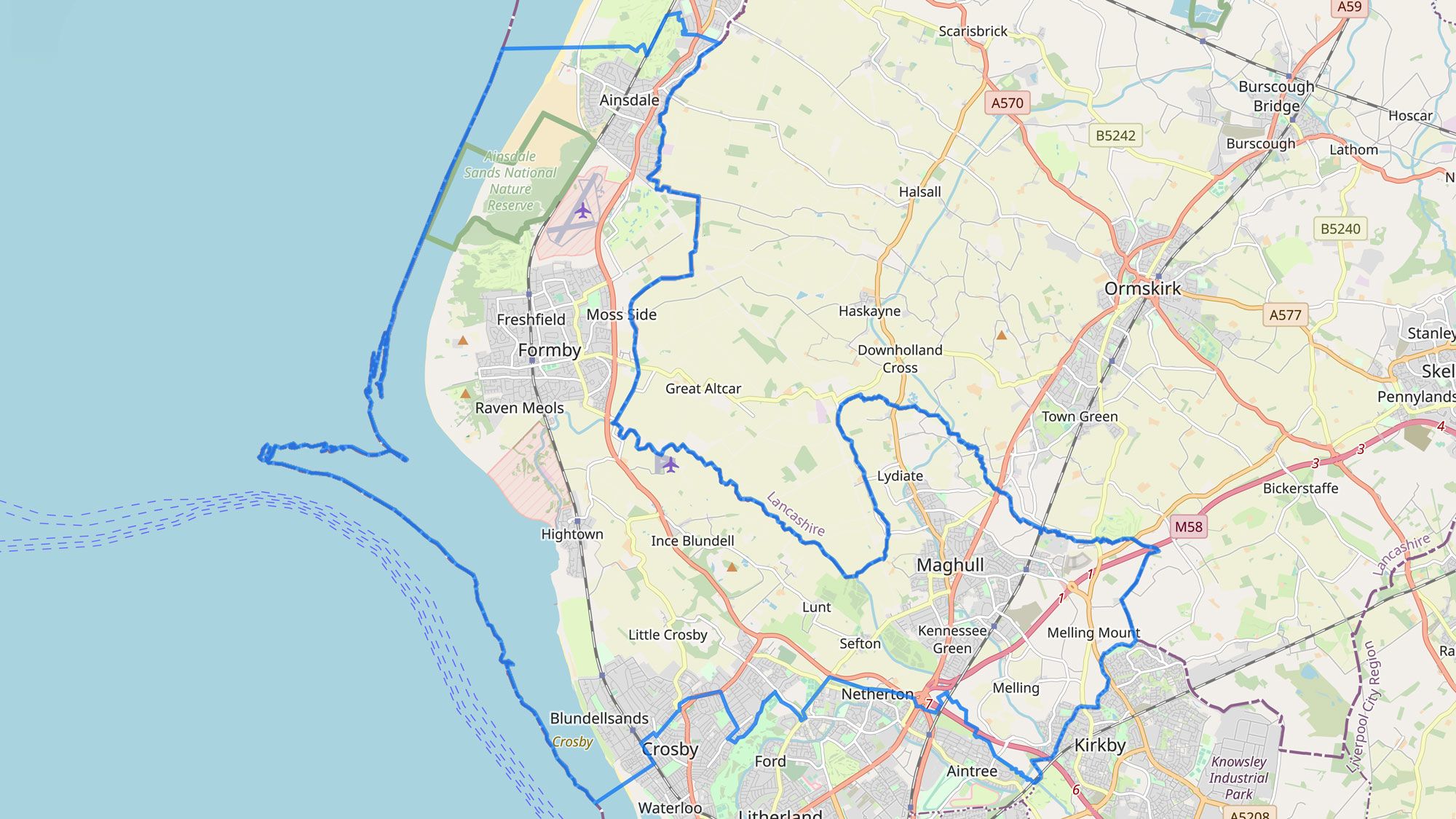

These comments were made about the Boundary Commission for England’s initial proposals. In response to these and around 45,000 other comments across England, the BCE released updated suggestions in November 2022. The commission again suggested Ainsdale should be removed from Southport’s parliamentary constituency and added to Sefton Central.

Proposed Boundary for Sefton Central

I wanted to know why. The report that accompanied the commission’s updated changes did little to help and even left me a little frustrated. The report acknowledges the opposition to removing Ainsdale from Southport. However, it doesn’t really address these concerns. Instead, it just moves on to talk about the proposal for Southport’s constituency to cross Merseyside and Lancashire’s boundary.

“We received approximately 200 representations in opposition to the inclusion of the Ainsdale ward in the Sefton Central constituency, with detailed evidence provided that this ward should be included with Southport (BCE‑90826, and Stephen Jowett – BCE‑77635). Some of these representations highlighted that both the Southport and Sefton Central constituencies are within the permitted electorate range and therefore do not need to change, but crossing the county boundary was supported by the Conservative Party (BCE‑86369), the Labour Party (BCE‑79505) and the Liberal Democrats (BCE‑97971).”

But breaking local ties and crossing regional boundaries are different matters. For me, the local ties between Southport and Ainsdale were simply acknowledged and then put to one side.

The problem for me, and anyone else attempting to understand the situation, is that the Boundary Commission for England is the only source of information for the justification of its recommendations. Without this information, can people really discuss the pros and cons of proposed changes? Is this sufficiently democratic?

For me, not providing this information doesn’t make sense for the commission. How can they gain informed comments from the public? Worse, it may be undermining trust in the BCE and the political system as a whole. Several comments on Ainsdale even described the recommendations as attempts at political manipulation and gerrymandering.

Me, back in town. Photo: Ray Woods

Me, back in town. Photo: Ray Woods

Left unsatisfied, I wanted to understand the situation better. I decided to travel back to Southport. But first, I wanted to find out more about the redrawing of constituencies.

Grand Redesigns

The electoral map in the UK is under review. A House of Commons Library briefing explains this current review of parliamentary constituencies started in January 2021 and must be finished by July 2023.

Given the latest recommendations, some parliamentary constituencies may change a lot.

Take Defence Secretary Ben Wallace’s seat, which may be abolished and divided up. Others may stay the same, like Southport’s neighbour West Lancashire.

The boundaries of constituencies are reviewed every so often, mainly to keep them in line with population and local government boundary changes. However, the current review is likely to result in significant change for many constituencies. The degree varies. But only 55 of England’s current 533 seats will remain completely unchanged.

How did we get here? It’s a bit complicated.

I turned to the House of Commons Library briefing to find out more.

In 2011, David Cameron and Nick Clegg’s coalition government gave future reviews the job of reducing the House of Commons to 600 seats.

The coalition government also wanted to make a vote in one constituency similar in influence to one in any other. To do this, they created a rule. This required that, with a few exceptions, all UK constituencies had to have a voter population that was 5% above or below the “electoral quota”.

This quota is basically the number you get when you divide the UK’s total number of registered voters by the number of constituencies.

Two reviews attempted to apply the 2011 changes. Both were cancelled before being implemented.

Image: Modified AI-generated images by Stable Diffusion 2.1

A parliamentary select committee looked at the 2011 changes. The House of Commons Library briefing notes that academics and others who talked to the committee said the changes would lead to “unprecedented disruption to the pattern of existing seats.” In their evidence, electoral geography expert Professor Ron Johnston and his colleague David Rossiter also said the major factor in this disruption was the 5% rule.

In 2020, following Brexit, Boris Johnson’s Conservative government adapted the rules again. It scrapped the 600-seat goal, saying the UK will continue to have 650 constituencies. But the government kept the 5% rule.

So far, I haven’t found out why it’s 5% and not something else, like 6%. It seems like an arbitrary number. Indeed, the Hansard Society for Parliamentary Democracy argued that the previous number for seats had been “plucked from thin air – 600 simply being a neat number”.

Still, each constituency now needs to have between 69,724 and 77,062 registered voters for parliamentary elections.

Image: Modified AI-generated image from Stable Diffusion 2.1

The current boundary review is significant. It will lead to a lot of boundary changes.

This is partly because the current review needs to follow new rules. But it’s also because it’s being done after a long period that has seen no boundary changes implemented.

The last implemented review was based on voter population data from February 2000. The current review is based on data from March 2020. A lot changed in these two decades. For example, according to the ONS, the UK gained an additional 3 million parliamentary voters.

The 2020 rules also changed how reviews are implemented. Previously, Parliament had a chance to vote on a draft of recommended changes before they went through. In 2020, this check was removed. Now, once a final draft is submitted to the King, the new boundaries come into effect the next time there’s a general election.

Graphic data sources: ONS. Electoral statistics, UK: December 2021 and Electoral statistics, UK: December 2020

The reviews are carried out by four boundary commissions, which have been setup to be independent and non-political public bodies.

Politicians can submit comments to the commissions on review recommendations. However, these comments are not supposed to carry any greater weight than those provided by the public.

Who’s losing seats? Who’s gaining?

The 5% rule means the number of seats across the UK will be allocated based on voter population. This doesn’t just affect boundaries. It also has an impact on each nation’s number of seats.

Under the current review, Scotland loses two seats. These losses are in addition to the 13 seats Scotland lost in the last review. Scotland will now have 57 constituencies. Their boundaries are looked at by the Boundary Commission for Scotland.

Wales will lose 8 seats and will have 32 constituencies after the current review. Its boundaries are checked by the Boundary Commission for Wales.

Northern Ireland will continue to have 18 seats. Its reviews are carried out by the Boundary Commission for Northern Ireland.

England’s review is performed by the Boundary Commission for England. It will gain ten constituencies. However, as the BCE sets out, these gains are not equally distributed across England.

For example, while the South East will gain seven seats, North West England will lose two.

And it’s here in the North West where I returned to Southport.

Journey to Southport

On the first morning of my trip back to Southport, I woke up to the news that there was a man on a roof just around the corner. When I walked towards the town centre, he was still there. Fire engines and police cars lined the side of the road. An area was cordoned off. There was debris from broken tiles on the road, thrown by the man, and smashed car windscreens.

Response to the man on the roof.

Response to the man on the roof.

A passer-by, walking along with her dog Bertie, mentioned to me that he’d been up there for hours. She was getting a little older, sporting short-dyed hair and wearing a long cream coat. Her house is opposite where all the commotion was going on. Men have it tough, she told me, they need more help.

When the conversation moved on, I mentioned the boundary changes. She was the first person I asked about them during my trip. She hadn’t heard about them. Instead, she responded by talking about how Southport was brought into Merseyside 50 years ago, and how the town was brought down by being linked with Bootle. She recalled how her property tax had gone up.

There’s a long memory of this boundary change in Southport. It took place against the wishes of many in the town. As I heard when growing up and during my return, it’s a story often entwined with the town’s decline.

The woman continued on to take Bertie for his walk. Later in the day, I checked the Liverpool Echo to see what I could find about the man on the roof. He’d been sectioned under the Mental Health Act.

During the next few days, I asked as many people as I could about the boundary changes and what was going on in the town. While off to a negative start, I hoped I would hear more positive stories.

The Response

In my attempt to get a grasp of what people in Southport thought about the suggested removal of Ainsdale, I hit an immediate barrier. Though a select few knew the boundary change review was happening, this was not typical. Nearly all of the people I asked said something like Catherine, Kirsty or Laura.

“I didn’t even know this was on the cards... Do you know why this is being proposed?”

“I’ll read up about it as I’ve not been paying attention really.”

“I don’t think I’ve heard about it before!”

People have a lot on. I wasn’t really surprised. But I didn’t want to give in just yet. I arranged a chat with Dorothy and Eric, a couple in their eighties who live in Ainsdale.

Eric and Dorothy

Eric and Dorothy

When I arrived at their home, Eric was tinkering away just outside their front door. It turned out that he’d just cut his finger. He invited me in. Inside, I was greeted with the smell of fresh baking. While Eric had worked as an electrician for Manweb, Dorothy had been a high school teacher, including in home economics. In search of a plaster, we made our way through to Eric and Dorothy’s neat kitchen and conservatory.

Dorothy offered me some biscuits she’d just baked, with a warning the amaretti ones could be soft in the middle. We settled down for our chat.

Dorothy told me they haven’t had much information about the boundary changes. She remembered reading about them in a local newspaper, which has since closed down.

She said she “was very concerned” when she first read about the changes. She’s lived almost her entire life in Southport, Eric his whole life. She has a clear view of what places the town includes, given the way it’s always seemed to be. One area is Ainsdale. When talking about other places in Southport, she said “they’re part of us and so why should we just be chopped off.”

Eric told me that “Southport has changed, we’ve seen its rapid decline.” One reason the couple think this has happened is by Southport joining Sefton Council. No wonder they were concerned about joining Sefton Central as a constituency. “We lost out with this joining Sefton”, Eric said.

Dorothy assumed the changes are being made for political reasons, given what she’s seen. “It’s just as though it’s being changed to the detriment of the people who live here, and we haven’t been asked.”

You can listen to what Eric and Dorothy had to say in the video below.

One person I talked to who was keenly aware of the boundary change recommendations was John Pugh. John was the Liberal Democratic MP for Southport for almost 16 years. He decided not to seek re-election in 2017, but he’s still in politics in the town. He’s now a local councillor.

On a grey November day, I made my way to Southport’s Lib Dem offices, which sit in a semi-detached building next to a shop selling blinds. When I arrived, the office appeared deserted, but I didn’t have to wait long for the sprightly John, who’s now in his mid-seventies. After quickly opening the office up, John tossed a few boxes off a pair of chairs and mentioned something about leaflet folding going on the night before.

We sat down in the space John had cleared, which had a view out onto the street.

“You’ve caught me at a precious moment, I was actually speaking to the boundary commission this morning”.

John explained that the Liberal Democrats had provided alternative recommendations to the boundary commission which they felt better reflected communities. John didn’t think the commission had given these suggestions much attention. “They seem to have bypassed them or completely ignored them, and so my final submission might be quite a rude one.” He explained he wanted to ask why the boundary commission even has a public consultation if they’re not going to address the results. He didn’t feel like he’d been heard.

Just as John was finishing his point, a series of high pitch beeps and a low rumbling announced the arrival of a bin lorry just outside. The lorry slowly filled the office’s window and, in so doing, revealed the name of Sefton Council on its side.

Sefton Council has been under Labour’s control since 2012. It serves as Southport’s local council and it’s not to be confused with the Sefton Central constituency where Ainsdale may end up.

The appearance of the council’s name reminded me of its less than positive response to the commission’s proposals.

Sefton Council wasn’t happy with a claim the commission made about the changes to Southport’s constituency. This claim was that the recommendations for Southport would allow the commission to “better respect both local ties and the boundaries of existing constituencies across Cheshire and southern Lancashire.” Sefton Council’s response was to overwhelmingly pass a motion that described this claim as “hogwash and an insult to the intelligence of local residents and representatives.”

Representatives from all the local political parties, the local council and the ward’s population seemed to be against the recommendations for Ainsdale. Given this opposition, it seemed important to me to understand what local ties and boundaries the commission was weighing those in Southport against.

Ainsdale Ward

I asked John Pugh what local ties the commission’s claim might be referring to. Despite his contact with the commission, he wasn’t sure. This left me wondering if anyone knew which ties the commission was talking about.

John wasn’t convinced that the commission had a clear sense of communities in the North West in general.

“I visualise them, maybe wrongly”, John told me, “as a lot of clever boffins in London who sit and look at maps and maybe draw some of their wrong conclusions from some of the maps they’re looking at. So although they do strive to embody communities, they don’t necessarily know what is and what isn’t a community.”

For John, the commission’s recommendations miss the mark on community ties. “I feel what they have done appears to be more the result of a bloodless mathematical exercise than an attempt to build parliamentary constituencies around a meaningful sense of community.”

For places like Southport, John felt this was significant. He acknowledged that the commission couldn’t always build constituencies around communities given the 5% rule. However, John also said people have been elected in Southport “by appearing to champion the town over and above their party”. If the commission’s recommendations go through, John thinks this is less likely to happen.

Then there’s the people of Ainsdale.

John conducted a survey in Ainsdale to see what people thought of the commission’s recommendations. An overwhelming majority opposed the changes. But by conducting the survey, John gained another impression. People in Ainsdale were struggling “to understand why they seem to have been singled out for isolation and removal from Southport”.

This made me think of Eric. He’d felt Southport had lost out by ending up under Sefton Council. The comments on the BCE website made it clear he wasn’t the only person in Ainsdale with this opinion. Now they were all going to be moved into the Sefton Central constituency. But many didn’t even understand why.

I didn’t either.

I continue my exploration of the voice of local communities in shaping their political boundaries in part two. I do so by describing what I’ve discovered by exploring local ties, boundary change history and key locations in and around my hometown.

To find out about this project’s other activities, please visit my website here. You can also find useful links for resources on UK political boundary changes and local news here.